Thursday, 1 April 2010

Vertical Zoo!!!

Tuesday, 30 March 2010

Confused transnational networks...

Sitting on the train from Edinburgh to London, using East Coast Mainline's free wireless. Apparently we have left the UK. Spotify has started playing Swedish adverts at me (very funny they are too, despite or because I don't understand them!). Another reminder that virtual and physical networks and spaces do not map 1:1 onto one another...

Week 10: Sprawl, Megacity, (Post)Urbanism

Jameson - Future City

Koolhaas - Junkspace

Lin - CHINESE ARCHITECT ©

This week’s readings take off where the previous ones left off, with the failure of urbanism to be able to deal with the urbanising trends of the third world, but also suburban sprawl and the economic conditions which create this new condition of ‘junkspace.’

Together, the Chinese Architect© and Junkspace portray a fascinating, if somewhat terrifying vision of potential futures of architecture. Through extreme commodification, the architect is transformed from the designer of buildings and spaces to someone who applies a given plan to a site. Despite the increased importance of Architecture©, the agency of the architect is heavily reduced – economics govern the structure of the city. Perhaps the only remaining recognisable role of the architect is in designing the ‘hat’ or skin that adorns the generic plan, or otherwise in creating one of the architectural ‘recipes’ which others then apply to their sites. But in Architecture© even these tasks are fully subservient to the economies of development, with a drive to the most economical designs, regardless of issues of comfort and well-being.

China designs and builds with a speed that for us is unimaginable. But the shocking compromise in quality sometimes reveals itself in the news. In this building collapse in Shanghai, perhaps the most worrying aspect is that in the background there stand numerous other identical buildings, all of which presumably share the same major error in the design of their foundations.

In Junkspace, Koolhaas addresses many of the same issues (albeit in more extreme forms) that concerned Calthorpe in his vision for the Next American Metropolis. However, whereas Calthorpe flees in terror, Koolaas’ acceptance of the condition of junkspace and the way in which he embraces the possibilities it offers makes it a much richer account, and although it is largely diagnostic, he begins to set up a vocabulary of architectural techniques to deal with the condition: “clamp, stick, fold, dump, glue, shoot, double, fuse.”

“We have made them [hospitals] (too) human; life or death decisions are taken in spaces that are relentlessly friendly, littered with fading bouquets, empty coffee cups, and yesterday’s papers.” – Junkspace, p. 185

Would you like a skinny cappuccino with your hip replacement, madam?

This extract reminded me strongly of a recent BBC news item on Foster’s new Circle hospital in Bath (above). According to the reporter, the hospital was designed to make it feel like a hotel, with the aroma of coffee in the reception to make people feel more at ease. Although there is something slightly strange and unnerving about the transformation of healthcare buildings into branches of Starbucks, if the quality of space has a positive effect on the health of patients, then perhaps this is not too bad after all.

Monday, 29 March 2010

Week 9: Morphology, History, (New)Urbanism

Calthorpe: The Next American Metropolis

Rossi: The Structure of Urban Artifacts

Rowe & Koetter: Crisis of the Object: Predicament of Texture

As I read through Calthorpe’s vision of the Next American Metropolis, I found myself becoming increasingly critical. He uses data to back up his argument, but I can’t help feeling that this often has his own spin on it. He claims that ‘the car wants to travel more’ (p. 27), quoting an 82% rise in vehicle miles against a 21% population growth between 1969 and 1990, but this is surely also bound up in the increasing affordability of the car and petrol, and increased car ownership, in part a lifestyle choice? His portrayal of a hierarchy of public and private buildings seemed too black and white to me, ignoring the increasingly complex nature of public/private space. And whilst I agree that commuting by train is preferable to each person driving to work, he seems to have a very romanticised idea about how comfortable this would be…

Calthorpe's preferred choice of reading location?

One interesting point of contention between the American Metropolis and Collage City concerned the nature of outdoor space. I am inclined to agree with Rowe and Koetter that an increased complexity of outdoor space is fundamentally more interesting than a barrier free expanse of public land. Calthorpe by contrast called for all exterior space (at least all that meets the street, given his strongly defined public and private spaces) to be in the public domain. He equates closed off spaces with the negative image of gated communities, which I do not think that Rowe and Koetter are advocating when they call for a complexity of outdoor space.

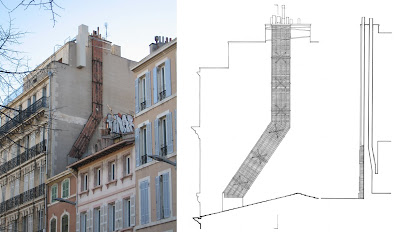

The main argument of the Crisis of the Object is that objects (which have valuable qualities despite their tendency to attempt neutrality to their urban context) should become part of the urban texture so that both figure and ground are enriched. Having seen today some images of Zaha Hadid’s proposal for Zürich Airport (and also thinking about her CMA-CGM tower in Marseille), it is evident that this idea is not universally held; the ego of the architect allows itself to be bigger than that of the city.

Zaha's object is obviously attempting to dissolve into the urban fabric of Marseille...

Throughout the Architecture of the City, there were constant implicit references to ideas from Umberto Eco (which it predates): the changing meanings of buildings over time, a split between function and type (semiotic implications of a church that is used as a cinema, for example). In some ways Rossi also shares common ideas with Latour, in that social relations are embedded in the architecture of the city. A lot about a city’s social and economic structures can be understood by looking at the patterns of land ownership across the city.

As Stephen pointed out with reference to Koolhaas in the lecture, figure ground plans are limited in that they only work on one level. My site in Marseille is a good example of this limitation, despite being in a historic city centre. Although demonstrating the density of the block at ground level, a figure ground plan would oversimplify the complexity of different private and semi-public spaces at higher levels.

Sunday, 28 March 2010

Spectacles of waste

Week 8: Entropy, Maintenance, Waste

Bataille: The Notion of Expenditure

Crisman: From industry to culture

Hetherington: Second-handedness: Consumption, disposal and absent presence

An interesting new comparison to the other museums discussed by Crisman would be Chipperfield’s refurbishment of the Neues Museum in Berlin. Although the project did not deal with the empty shell of an industrial building, many similar issues would have been tackled, such as what to restore and what to replace, as well as the relationship between the building and the objects on display.

“The museum is above all a conduit of disposal.” Hetherington, p. 166

For me, this statement provides a radical new way of understanding the programmatic nature of museums that has strong implications on their design. It becomes all the more interesting when the museum itself is built in a recycled shell, since whilst it holds objects before disposal, the museum itself also undergoes a process of disposal and decay (perhaps more so than a complete new build). Both Hetherington and Crisman touched on ideas from Eco’s text on the semiotics of architecture, acknowledging that a building’s meaning and value is not a constant, but changes over time.

In my 4th year project on the Edinburgh Kitchen, I worked with Olly Cooper to study the contrast between a typical architect’s conception of an immaculate kitchen against the reality of a lived-in kitchen and its own landscapes of dirt. It reminded us of the difference between our ideas and the messy reality of life, as well as highlighting the different forms and materials that take dirt differently – which are the areas of a room that are always dirty, and do they need to be designed differently? Are there areas where dirt is acceptable? In Crisman’s essay, as well as in Auer’s ideas on plastics, we were reminded about the futility of attempting to control weathering in materials. In the Dia:Beacon, the scrupulously cleaned brick has become covered with a white efflorescence.

Musicians tend to deal with entropy much more directly than architects. For a note to be sustained over a longer period of time, more input is required from a musician. With string instruments, this is done through bowing technique. The ends of notes are even more significant in ensemble music, since if all musicians do not end simultaneously, the result is a ragged performance. Ligeti created a musical equivalent to Robert Smithson’s Asphalt Rundown in his work, Poème Symphonique, in which 100 metronomes are wound up and released simultaneously, slowing to a halt over about 20 minutes. Although his primary interest is in the rhythmic patterns created by mechanical imperfections, this piece could also be read as a study of the entropic condition of musical production.

Tuesday, 23 March 2010

Topical megacities

Saturday, 13 March 2010

Week 7: Material, Immaterial, Virtual

Sunday, 7 March 2010

Baugeist, lost in translation...

Vogt Landschaftsarchitekten - Lecture, 04.03.10

Thursday, 4 March 2010

Week 6: Technology, Infrastructure, Hardware

Wednesday, 3 March 2010

Week 6: Failed to open page

Tuesday, 2 March 2010

Week 6 (preview...)

Thursday, 25 February 2010

Week 5 (contd.): Kitsch...

Wednesday, 24 February 2010

Week 5: Affect, Atmosphere, Sensibility

Wednesday, 17 February 2010

Week 4: Programme, Event, Gesture

Sunday, 14 February 2010

Week 3: Signs, Semiotics, Signification

Wednesday, 10 February 2010

E-Day reviews, and couple of other things...

Thursday, 4 February 2010

Week 2: Capsules, Networks, Surveillance